Which capabilities to prioritize when implementing merchandising systems

Feb 21, 2024 • 11 min

As a retailer grows and matures, they will inevitably find themselves needing to invest in updated technology to support the needs of their merchandising team. When it comes to technology, the entire process chain, from planning to execution, is often taken as a whole.

Planning systems typically include financial, merchandise, and assortment planning support and additional supplemental planning around those. Execution systems, on the other hand, are about forecasting, allocation, and replenishment (DC & store) and may offer additional tools to support those processes.

Even if a retailer decides to invest in all these areas simultaneously, it is unlikely they can implement the technology and absorb the changes brought about by all of them simultaneously. The question then becomes, “Which capabilities should we implement first?”

Intuitively, it makes sense to start at the beginning of the process, get planning support in place, and then work downstream. However, that may not be the most effective approach in many situations. Below, we’ll outline some things to consider when deciding where to start. While many subsets of analytics and optimization can influence these processes, we will focus on the core processes for simplicity’s sake.

Traditional merchandising systems

Traditional merchandising systems are loosely integrated, with plans driving top-down decision-making followed by bottom-up execution of those plans with the help of a statistical forecast. Understanding how the technology relates to the main decision points is an important starting point.

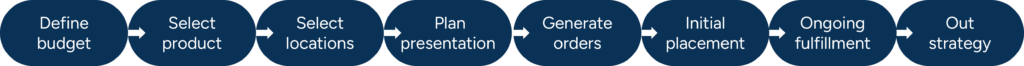

Below is one way to think of the typical decision points needed to procure and place products:

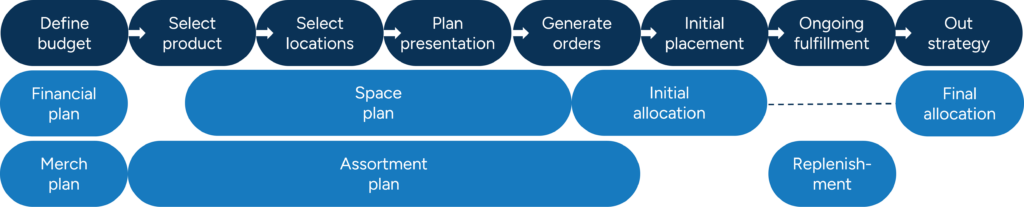

Each of these decision points is supported by technology. As technology and retail science have matured, the application of technology to these areas has shifted. A traditional view of the technology mapping to these processes in a specialty retail environment would look something like this:

Planners set up purchasing budgets through a top-down process. They break down the company’s financial plan into a more detailed merchandise plan that becomes each buyer’s, planner’s, or allocator’s budget or “checkbook” of what they can spend.

They then build out the offer to the customer using assortment plans, which effectively work from mid-level product planning criteria. Sometimes referred to as a “middle-out” process, this uses criteria such as style or color rather than SKU-level (bottom) or department or division-level (top) criteria, and at mid-level location groups/clusters rather than at individual stores/channels (bottom) or the entire company (top).

This process aligns the planned product purchases with the previously agreed merchandise plan and the allocations typically created at the bottom. Frequently, variations on these plans will supplement the process, including open-to-buy plans, inventory-flow plans, key-item or ladder plans, and space plans representing the presentation requirements for each location.

In a traditional setting, the assortment plan carries significant weight in the decision process, covering everything from what to buy, where to offer it, how much to buy, when to move it, and how to place it initially.

An allocation system sometimes provides the first true, bottom-up view of what specific stores or channels need by spreading the proposed purchase order among stores. This step helps to ensure that what’s proposed in the assortment plan properly considers the needs and capacity of stores before committing to the order. The initial allocation is then either driven by the assortment or the allocation that validated the assortment.

Once a product lifecycle begins, a replenishment system frequently supports it by tracking store- and channel-level selling, forecasting future activity and inventory requirements, and ensuring inventory is in place to meet changing demand. In many cases, this is the first point in a traditional retail environment where the art of merchandising meets the ‘science’ of retail in the form of technology. Many retailers shortcut this process by using an allocation system to cover the replenishment of a product within its lifecycle.

Finally, at the end of a product’s life, before markdowns occur, any remaining inventory is pushed out, usually by the allocation system, ideally to the stores most likely to sell it.

An evolution of merchandising processes

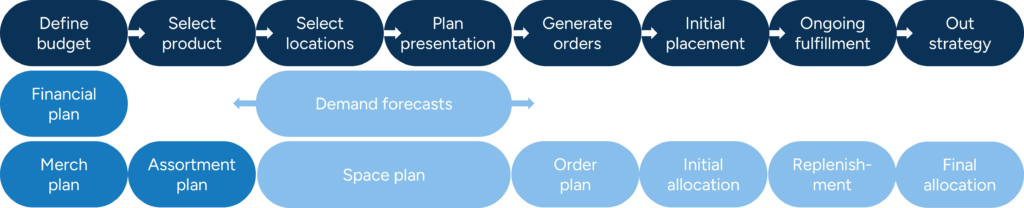

Retail ‘science’, technology, and process have evolved to the point where many retailers are rethinking how they fit together. In part, this reevaluation is because, as an industry, we have struggled to find a genuinely effective assortment planning tool. That struggle is mainly due to our trying to make those tools do too much at once. In addition, technology has evolved to enable us to apply a more scientific approach and bottom-up understanding of the process. Putting these two things together allows us to rethink and simplify the process, as illustrated below:

Looking at the illustration from right to left, final allocations, replenishment, and initial allocations utilize modern technology to optimize their results for their intended purpose. The forecast, often traditionally embedded in, and only helpful for, replenishment, has now been optimized individually for different product types and can support allocation and planning processes in addition to replenishment.

Well-thought-out solutions have integrated these three processes, not just from a data perspective but functionally as well. Functional integration unifies the look and feel of processes, making it easier for users to manage them from end to end. In contrast, historically, there was often a split, meaning that different processes, such as replenishment and allocation, needed dedicated expert users.

This configuration also enables planners to apply the logic needed to generate an order plan driven by the forecast. They can then analyze the details of more accurate store forecasts and create an inventory plan considering real-world constraints such as presentation requirements, pack configurations and lead times. The result is a new bridge between the ‘art’ and the ‘science’, where bottom-up details are married and automatically rationalized with the top-down plan while generating a more accurate order quantity.

The pressures on the assortment plan, in terms of generating order quantities, breaking that down into individual orders and managing the initial allocations, have now been significantly reduced. The focus then becomes the ‘what’ to buy and the ‘where’ to make the offer. While sales volume can inform this decision, attempting to get a precisely accurate volume is no longer necessary to drive ordering.

A more modern approach shares some assortment localization planning by utilizing a space planning solution that can tailor an enterprise assortment to each location’s specific needs, again easing the load on the traditional view of assortment planning. The order planning process will take the product and its offering location to generate a more precise order quantity.

The characteristics of products and the relative volumes of the items in the assortment plan can guide the order plan to adhere to the buyer’s (or planner/allocator’s) intent when assembling the assortment. In some cases, higher-level forecasts and iterations of the detailed forecast can also validate the assortment.

The top-down planning process remains in place, with support from forecasting mechanisms that provide a check and balance or even guidance.

The numbers game

Let’s compare the three major merchandising components to understand what will ultimately be influenced. Take, for example, a retailer offering a range of fashion and general merchandise with three distribution centers (DCs) and 500 stores. Supply chain professionals in different sectors, companies, and departments will see the following activities somewhat differently. Still, for this example, they are broken down into assorting, ordering, and allocating/replenishing, as defined below.

Assortment planning (10 Decisions)

For the purposes of this discussion, assortment planning refers to determining what products to offer. Generally, the primary objective is to decide what products to buy or not to buy. If we include decisions around ranging (which stores get the products we select), then we also make this choice for the stores.

In virtually all retail environments, stores are clustered into groups by sales volume, demographics, geography, or similar criteria. If, for the sake of this example, we assume 10 of these groups, then we’re making 10 ‘include or exclude’ decisions per product. The difference in what products to order is unlikely to be significantly altered using an assortment planning system.

The decision that will typically have the most significant impact on the quality of the result is the grouping of the stores. Beyond that, the most substantial benefits come from the consistency of the process and having all the data held in a single merchandising system for easy comparison.

Space planning (500 Decisions)

Separating the store-specific component of assortment planning and utilizing space plans to get to store-specific planograms yield significantly better results. This improvement is due to eliminating inefficient use of space per location by matching the presentation of a product to its unique velocity in each location.

The most effective approach to this method uses forecasts rather than just historical sales data. However, getting to store specifics explodes the number of decisions planners must make. In this example, there are 500 locations rather than 10. Thus, planners have 500 decisions to make.

Ordering (12 Decisions)

Ordering refers to determining how many items selected in assortment planning should ship to a warehouse or DC at any given time. Here, we’re making the same number of decisions as the number of DCs multiplied by the number of receipts we plan. In an environment with 1/3 of products being one shipment (only received once in the DCs), 1/3 being two shipments (having a second DC receipt for fill-in), and 1/3 being ongoing basics, we may have an average of, let’s say, four receipts per product.

If we have three DCs, that’s a dozen decisions per product (3 * 4 = 12). Here is where technology can begin to have a more significant impact on the actual results. Especially in the evolved process described above, we’ll match the quantity ordered more closely to the future demand by store/channel and the constraints around them.

Allocation and replenishment (2,000 Decisions)

Allocation and replenishment refers to determining how much available inventory goes to each store. Here, we also have decisions to make for each receipt. If we use the average of four receipts from above, we need to make a store-specific choice for each store for each of those receipts.

In a chain with 500 stores, we’re now talking about 2,000 decisions (500 * 4 = 2,000). In the case of direct-to-store ordering, generally, allocation is combining the ordering and allocation steps. Ultimately, the difference in applying technology is moving a few units or case packs from stores that would sit on them to stores that would successfully sell them. That may not seem like much at first glance, but doing that with each receipt of each product typically represents millions, if not tens of millions of dollars of additional profit to a retailer of this scale before the capital savings that come from holding less inventory overall.

Using the above logic, we clearly see many more decisions in the allocation process than in ordering and assorting. Each activity has multiple considerations, but ultimately, allocation has more instances where good decisions can be helpful or, perhaps more importantly, where bad decisions can be detrimental.

Time to value

Poor allocation decisions can quickly ruin a good product purchase. As technology and processes have evolved, data has more opportunities to drive activity into allocation processes. We can now automate most allocation scenarios by using parameters that can often be preconfigured or sourced and integrated from other existing processes.

Merchandising systems can make more detailed evaluations of the many small decisions made in allocation and replenishment scenarios and then systemically validate those decisions, with only exceptional situations requiring attention from an end user. Planners spend less time on manual tasks, and the results are better.

In addition to saving time on the process side of allocating, modern technology has shortened implementation timelines for allocation, replenishment, and order planning technologies, especially in SaaS environments. Some modern allocation systems can be up and running and return on investment in a matter of months. Organizations can pilot the solution within part of the business or its operations and roll it out as quickly as they can absorb the changes. When existing processes have left some stores with far more inventory than they can sell and others with far less, analytically driven stock balancing logic can drive immediate gains.

Even today, assortment planning projects can take well over a year (sometimes several years) to get up and running. This extended timetable is partly due to the higher degree of “art” in the assortment process, which varies dramatically from retailer to retailer – and often even across merchants, such as buyers, planners, and assorters, within retailers. Suppose we replace the localization component with automated space planning. In that case, we further reduce the load on the assortment process, thus simplifying it more, making it more straightforward to implement and introducing a science-based approach to the lowest level of detail.

Measuring the value achieved in fulfillment and ordering is more straightforward as well. Since decisions are now primarily based on data, we can easily calculate the results against earlier data and determine how much value the new technology and processes are delivering. Measuring the return from planning processes has historically been very subjective; therefore, the resulting value measurement is far from empirical.

So, which comes first?

What if a retailer is in an environment where they need help in all three of these areas? Which should they focus on first? Each situation is unique, and their choice depends on their current capabilities and proficiency. Generally, there are two reasons why it makes sense in most cases to focus on allocation and replenishment first and work upstream to ordering, followed by planning disciplines.

The first reason goes back to “the numbers game” section above. The more chances there are to improve the quality of the decision, the more impact there is on the bottom line. Of course, if a retailer does a better job choosing the “perfect product”, it will likely result in better performance. However, merchants rarely miss choices with such dramatic influence in the assortment planning process. It’s much more common that over-assortment is an issue.

The second reason to consider allocation and replenishment first is that if a retailer makes the “perfect” assortment choices and even creates ideal orders to DCs, poor allocation can still irreparably damage the results. If, however, they make “good” decisions on assortment and ordering (which is common since there are fewer choices to make and, therefore, more thought going into each), improved allocation can make the best of what they ultimately end up with.

If done well, these improvements can almost always have more impact than changes to ordering and assorting processes. The possible exception is applying the evolved order planning process described previously, which can feed the allocation process with more appropriate available inventory levels.

We should consider space planning next for similar reasons. Making hundreds of better decisions has a higher likelihood of a positive impact. As suggested above, if a product’s presentation isn’t conducive to buyers’ expectations, or if shelves are empty because planners didn’t allocate enough space and inventory is in back rooms, we can negate the impact of upstream decisions regardless of how good they were.

Further, starting at the end and working up can generate enough return to fund investment in the other two areas as time permits, and the business can absorb the changes.

Retail continues to change and evolve

Complexity is the reality of today’s retail landscape, and customer behavior is changing at a pace never seen in retail. Between economic influences, brand loyalties, channel competition, fashion preferences, and other factors, today’s customers are more unpredictable than ever. This change is felt differently at each store, so it is essential to have visibility into those changes and the ability to respond to them immediately. The bottom-up forecasting, allocation, and replenishment processes are the last chance to identify and react, getting retailers as close as possible to meeting the demand their customers represent. The last chance to get it right is the first place to invest in doing a better job.